Research Projects

Redirection of gesture trajectories between local and remote environments in mixed/augmented reality

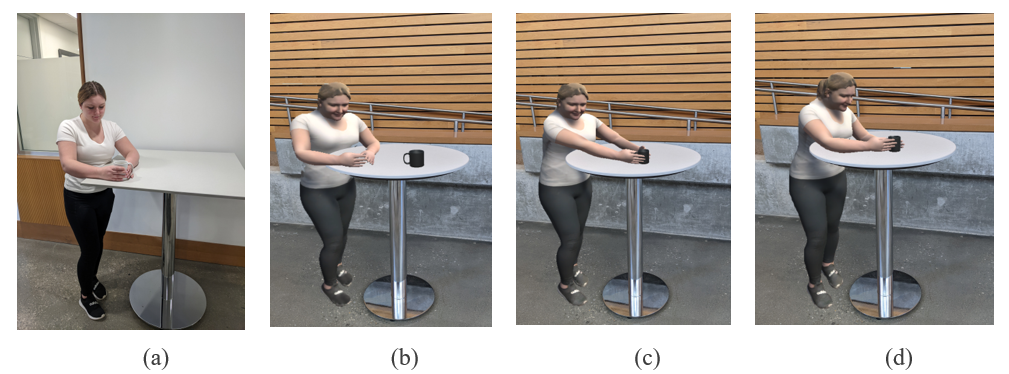

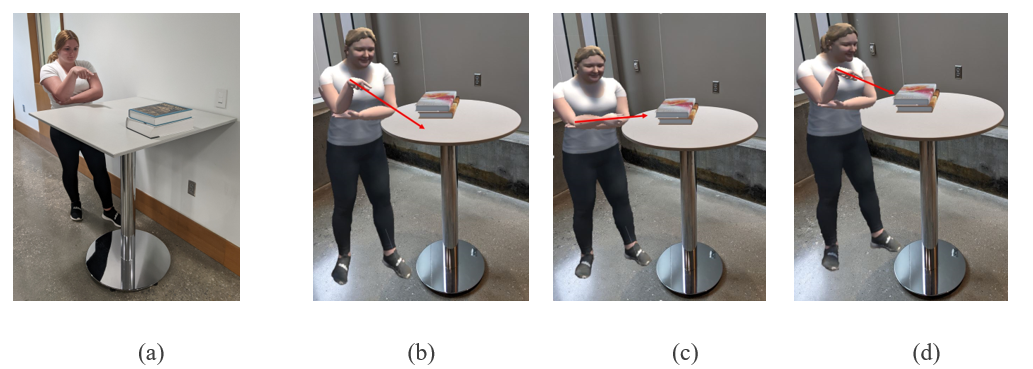

The above figures show the redirection of a user's gestures from remote to local environments (and vice versa) for avatar-based telepresence interactions. Gestural interactions can be divided into two types: i) positional interactions (Fig. 1) and ii) pointing interactions (Fig. 2). Positional interactions are interactions where the user has physical contact with an object in their environment. For example, picking up a chess piece. Pointing interactions are interactions where the user points at a particular object in their environment. Both these interactions need to be mapped onto the user’s avatar, in its environment, such that the interaction has its original intended meaning while also preserving the original nonverbal bodypose behavior. During my PhD, I proposed a multiobjective optimization approach using genetic algorithms to solve this problem for both positional and pointing gestures.

Generation of naturalistic locomotion paths between local and remote environments in mixed/augmented reality

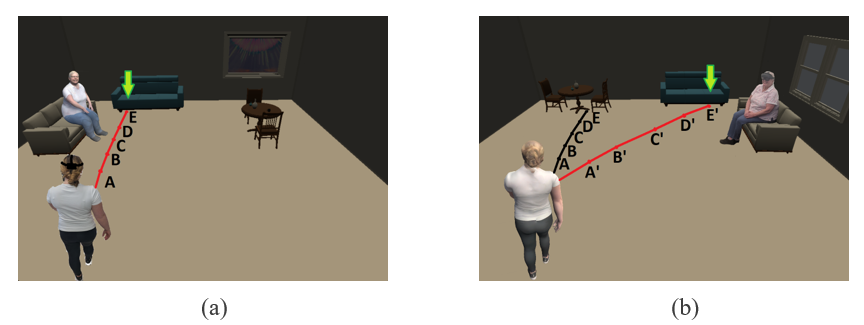

Remote mixed reality (RMR) allows users to be present and interact in other users’ environments through their photorealistic avatars. Common interaction objects are placed on surfaces in each user's environments and interacting with these objects require users to walk towards them. However, since the user's and their avatar's room's spatial configuration are not exactly similar, for a particular user's walking path, an equivalent path must be found in the avatar's environment, according to its environment's spatial configuration (Fig. 3). During my PhD, I proposed the use of the concept of mesh deformation to obtain this path, where we deform the mesh associated with the user's environment to fit to the spatial configuration of the avatar's environment. This gives us the corresponding mapping of every point between the two environments from which the equivalent path can be generated. The generated equivalent path serves as a reference for the avatar to follow. It needs to be modulated to fit naturalistic constraints, which is an active area of my ongoing research.

Redirection of locomotion paths for obstacle avoidance in remote augmented/mixed reality

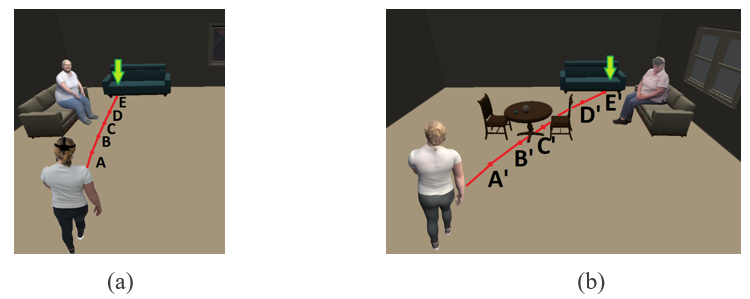

Obstacles in the context of remote-local AR scenarios are non-walkable spaces that consist of no interactable objects. Therefore, they do not serve any function from the perspective of mapping the user’s interaction from their environment to that of the avatar’s. However, the presence of obstacles can cause problems during mapping of locomotion between environments. First, obstacles can be of any irregular shapes and can occur in any configurations. Second, obstacles can be in either the avatar’s or the user’s environment and may not have any corresponding equivalent objects between the environments. This non-correspondence between the user’s and avatar’s environment can make the computation when finding equivalent paths complex. Moreover, we have presented the case for only two environments, i.e., the user’s and the avatar’s. However, it is likely that multiple users would be present in the interaction, where the equivalent locomotion mapping would get even more complicated. Thus, it is of great importance to automatically redirect walkable paths around the obstacles. During my PhD, I proposed an ellipse based solution that can modify the path smoothly around any irregularly shaped obstacle.

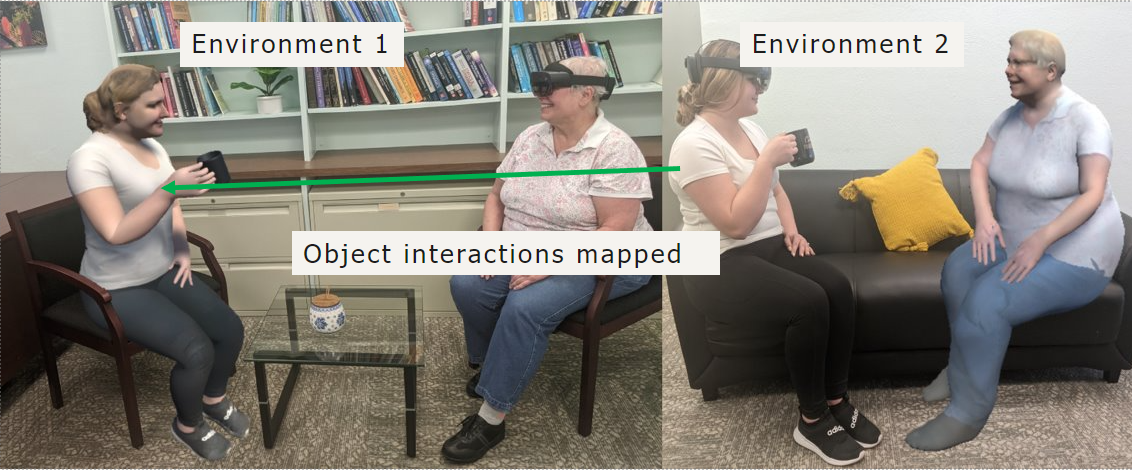

Older and younger adult perceptions towards HMD based telepresence interaction in collaborative AR

The aim of this project is to obtain the perceptions of older adults, with younger adults being the control when interacting with a photorealistic avatar of a remote user. In addition to their perception, we are also interested to know whether full body emotions and gestures expressed through the avatar are discernable to the older adults. The system involves real-time bidirectional communication of the participants with a remote user and was developed using the Unity game engine. The facial and body expressions are captured and transferred across the network using a ZeroMQ distributed computing architecture.

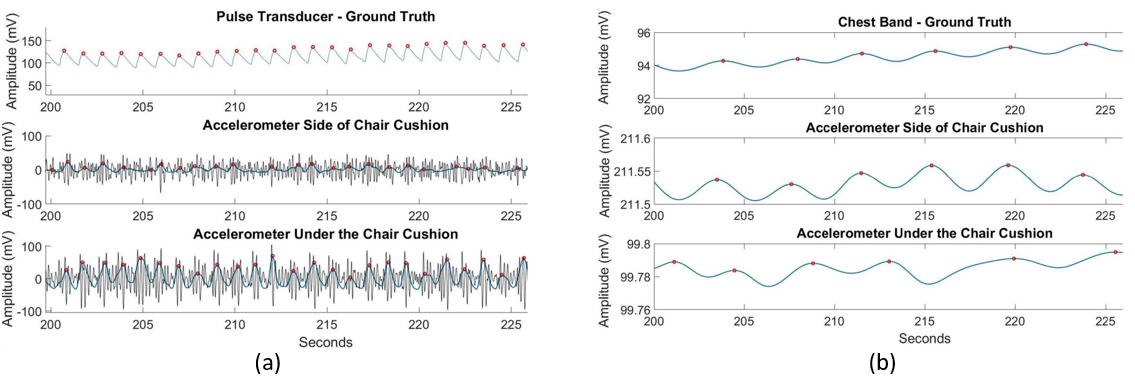

Non-invasive sensing of vital signs from recliner chairs

In this project, I developed a sensor system for recliner chairs that can extract the heart and respiration rates of the occupant in real-time. The system uses two accelerometers placed strategically to capture these vital signs noninvasively and without direct contact with the body, while at the same time, being hidden from view. The system was tested with 45 subjects, having an average age of 78.8 (S.D. = 12.5) years, for both upright and reclined configurations of the chair. We also tested the system on 6 different types of recliner models. The ground truth signal for the heart and respiratory rates were obtained using a piezoelectric finger transducer and thorax chest belt respectively. The mean heartbeat error for 45 subjects was 0.6 ms with an average error rate of 3.6% (p value = 0.00081, significance level = 0.05). Similarly, the mean respiratory breath error was 4.2 ms with an average detection error rate of 6.25% (p value = 0.032, signifcance level = 0.05).

Iterative participatory design of collaborative AR activities for older adults at long-term care (LTC) settings

This project involves developing collaborative activities in remote augmented reality that are adapted to the needs of older adults at long-term care (LTC) settings. The long term goal is for their friends and family to remotely interact with them via 3D virtual visits in AR through their photorealistic avatars. The hypothesis is that the immersive and collaborative nature of the interaction with loved ones will promote social connectedness and mitigate loneliness. The project follows an iterative approach of prototyping and refining activities in AR, with inputs from all involved stakeholders, including staff and family members of the older adults at LTC settings.